HUBER MAGAZINE

News & Podcasts

Locations

YOUR JEWELLER FOR LUXURY WATCHES AND JEWELLERY IN LIECHTENSTEIN, SWITZERLAND AND AUSTRIA

-

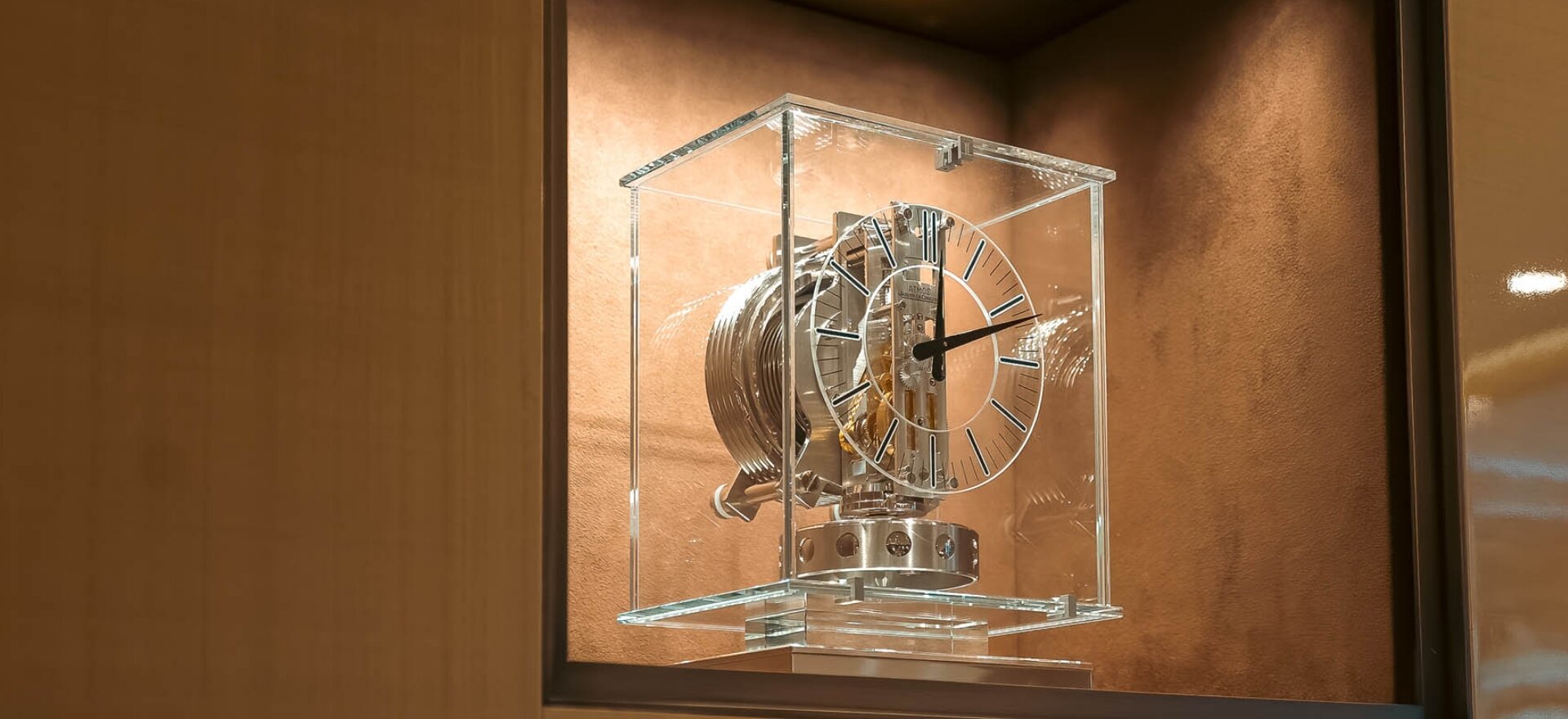

WORLD OF WATCHES

Städtle 11, FL-9490 Vaduz

T +423 237 14 14

WhatsApp +41 79 814 3613

welcome@huber.li -

HUBER BREGENZ

Kirchstraße 1, AT-6900 Bregenz

T +43 5574 23 9 32

WhatsApp +43 664 5353 268

welcome@huber-juwelier.at -

HUBER BREGENZ

Rathausstrasse 7, AT-6900 Bregenz

T +43 5574 23 9 32

WhatsApp +43 664 158 61 35

welcome@huber-juwelier.at -

HUBER LECH

Dorf Nr. 115, 6764 Lech am Arlberg

T +43 5583 37 37

WhatsApp +43 664 236 1146

welcome@huber-juwelier.at